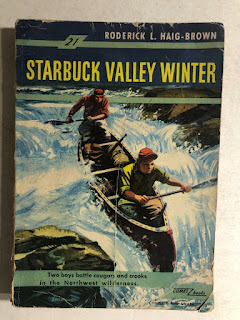

Roderick Haig-Brown, Starbuck Valley Winter

Books are dream factories, time machines, alternate universes, and slowly rotting carbon. (That “old book” smell is the smell of decay, with the books releasing in their erosion myriad volatile organic compounds like toluene, vanillin, furfural.) Books, even celebrated ones, don’t always keep getting read.

And there was a time here in British Columbia, gentle reader, when prolific author and prominent public figure Roderick Haig-Brown was all that and a bag of chips, but those days are no more.

The author of more than 25 books along with hundreds of articles, and not just a magistrate for 30 years but also a prominent conservationist, Haig-Brown’s name has been assigned to university buildings, mountains, a provincial park (before it was given instead, quite rightly, a name from the local Secwepulemc language, Tsútswecw), one of the annual awards from the BC and Yukon Book Prizes, even a fly-fishing association. He twice won the Canadian Library Association Book of the Year for Children Award (in 1947, which was the award’s first year, and in 1963), and he was a regular writer in The Atlantic and was even featured in Life magazine, so his fame spread well outside BC.1(It’s even said that Haig-Brown won the 1948 Governor-General’s Award for Saltwater Summer, Canada’s highest honour for writers, in the category that in the 1940s was called “juvenile fiction.” But that’s not quite accurate, because there wasn’t such a category in 1948. Instead, according to Andrew David Irvine, “Haig-Brown was likely the first (and to date the only) author to receive a Governor General’s Citation for his work,” and there’s no way at this distance to tell what the Governor-General meant by giving him this unique citation.)

Somehow, though, all of this doesn’t generally protect his readers now from the special kind of ignominy that comes from asking after him in a second-hand bookstore and having a clerk say, most often, “Who?”

I’ll leave for another day the story of how this knockabout vagabond Englishman came to be a Canadian magistrate, and to be invited to write an official government report that became The Living Land: An Account of the Natural Resources of British Columbia, only five years after which he lambasted the same government for what he saw as their core beliefs:

“The shoddy, uncaring development of our natural resources, the chamber of commerce mentality which favors short-term material gain over all other consideration, the utter contempt for human values of every kind.” (read more here!)

Great stuff, that.

And yet Haig-Brown’s fiction has mostly sunk from view. His writing about fish, fishing, and rivers hasn’t quite met the same fate, most of that at least loosely nonfictional, but I don’t think I’m wrong to call it greatly admired but not much read. The thing is, at this point I don’t know who wants to read something like Starbuck Valley Winter, and for all kinds of perfectly valid reasons of cultural change and environmental change.

In other words, I’m being genuine when I ask the question from my subtitle up there: what should a review say, when it’s possible that no one else on Earth will read this book this year?

To sum up the plot of Starbuck Valley Winter: young Don Morgan, whose father has passed away three years before the events of our novel, leaving him with his quietly wise Uncle Joe and sharp-tongued Aunt Maude, wants to make a man of himself and therefore heads for the wilderness (though not unduly far from town).

It’s the 1930s, and at 16 Don has dropped out of high school and is looking for work. After having spent the summer working alone on a small fishboat, he wants to earn the money for a larger boat, so he manages to claim a trapline. More or less, the novel charts Don’s adventures as he tries to establish this trapline: facing down dangerous wildlife, skinning the small fur-bearing animals that he traps, dealing with an unfriendly competitor, and living rough in the bush. Will he earn the necessary money? Enquiring minds want to know!

See the readership problem?

If you’re someone who wants to read about nature, you’re probably not a hunter, and you’re almost certainly not a trapper. If you’re someone who hunts and traps, you’re unlikely to want to read novels about the experience, certainly not 80-year-old novels by someone who’s labelled “conservationist” by every conceivable internet search about him.

But speaking as someone who grew up reading ripping yarns along these lines, like Zane Grey’s Roping Lions in the Grand Canyon (guess what it’s about, go on, you’ll never guess), and who used to fish, went hunting unsuccessfully a few times, and grew up back of beyond, Starbuck Valley Winter has a piercingly nostalgic feel. This is an ice-cream scoop of old-time Vancouver Island, but it’s readily understood by anyone who’s spent five minutes thinking about the last stages of what settlers could’ve considered the North American frontier, anywhere from California to Alaska.

And so yes, absolutely its erasure of Indigenous peoples and voices is nearly total. At a couple of points, one character compliments another by saying that it was “mighty white” of him. There are two female characters, among the large number of men: one is older and married, with a sharp tongue but a good heart; the other is a teenager, quiet and a bit emotional, who at 16 knows already who she’ll marry once her family can be persuaded to look on him positively.

It’s a mark of settler privilege, and of the age-related privilege that’s gradually accruing to we increasingly arthritic members of Generation X, that even though I recognize these various marks of shame, I can still get completely swept up in a book like Starbuck Valley Winter.

Roderick Haig-Brown was a hugely important figure in the invention of settler British Columbia as a place of conservation, and I don’t think environmentalism (or the environmental humanities, my academic home) has made anything like enough of an effort to come to terms with his complicated legacy. I need to write that book, among others goddammit, if no one else will, but for now, I’ll just enjoy reading this deeply flawed, deeply enjoyable, creakily obsolete Goldberg machine of a novel.

(You know you want to read it, too! Or maybe it'd be easier to read my own post about his loggers' romance novel Timber, or his lovely memoir-ish Measure of the Year.)

(Cross-posted over on my Substack, if you're one of those.)

Comments