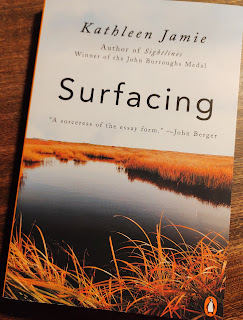

Kathleen Jamie, Surfacing

The reviews are mostly correct, in saying that Kathleen Jamie's linked essay collection Surfacing is both a thoughtful and a delightful read.

Writing in The Scotsman, Allan Massie remarks on the book's deep sense of gravity and time: "Jamie is concerned with the worlds we have lost, barely remember, yet seek to recover, and the world we have made and are in danger of destroying." In essence, Jamie travels all over the world to places where either we're uncovering ancient cultures that were lost in place, or where we're burying contemporary cultures in place, looking at these points of calamity with clearer eyes than I could ever manage.

In spite of its subjects though, or perhaps because of it, this is a writerly book and an achievement and something of a joy: "the whole thing shimmers," as Tim Hannigan suggests in The Asian Review of Books. Jamie specializes in a practical-seeming prose that doesn't dissolve when you spend some time with it. The more you read her pieces, the more you come to unpack from what looked straightforward the first time through, but the first time's never a puzzle and so is always rewarding.

But still.

I blame myself, of course.

Once again, though, I did sense a little of what I complained about recently in relation to Matt Gaw's Under the Stars, namely the limits that I'm feeling these days in nature writing's dedication to intimacy between writer and reader, writer and subject. Yes, as author you've seen this, and now as reader I'm seeing this, and as readers many of us are individually seeing this, but the uncertainty principle doesn't apply much beyond subatomic scales. Unless we're talking electrons, the mere act of looking at something doesn't necessarily effect change, so what are we doing here?

If you'll pardon the obscure reference, essentially I think we nature readers are all a bit Rob McKenna, in Douglas Adams' So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish. McKenna is a Rain God, except that he's a British lorry driver who doesn't know he's a Rain God and hasn't realized that clouds literally follow him all over the planet. When we briefly first meet him, he drenches a pedestrian with his lorry:

“For a moment he felt good about this. A moment or two later he felt bad about feeling good about it. Then he felt good about feeling bad about feeling good about it and, satisfied, drove on into the night.”

For there's an odd and troubling pleasure, buried in the masochism of environmental reading. The prose of wonderful writers like Kathleen Jamie, insightful and gorgeous as it is, gives me something I'd like to blame, but really it's me. The fine quality of their style makes me feel good while I'm reading, then bad about feeling good when reading about this terrible thing, then good about feeling bad for same, and am I doing much more than only reading? No, but to paraphrase something I'll be posting before long once I finish writing up Chris Turner's How to Be a Climate Optimist, maybe they also serve who only sit and read. (His book's more complicated than that, though my review probably won't be.)

Anyway, I blame myself for not getting as deeply into this lovely collection as it seems virtually all of its other readers have. I've been finding myself unwillingly reminiscing about the time I've spent reading about Quinhagak, for example, in spite of my grumping. Don't mind me, genuinely. In Surfacing, Kathleen Jamie has written a stunning book, and I'm sure you'll spend many a pleasant summer or winter evening reading and reading its essays.

In the right frame of mind, so will I again, I hope.

Comments