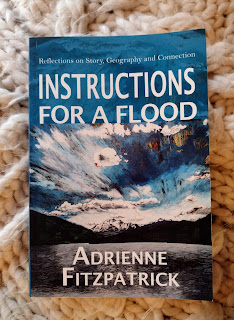

Adrienne Fitzpatrick, Instructions for a Flood

If you were looking for a small press whose books can teach you about place, you’ll never do better than Caitlin Press.

When I say that, I don’t mean simply British Columbia, or more specifically the BC interior region, though that’s the focus of many Caitlin books, but place in the abstract. If you read a handful of their books, you’ll know deeply what it means to live somewhere. Caitlin’s current editorship under Vici Johnstone has been remarkable, and as a result, it’s clear even before you begin that you’re in for a treat when you pick up Adrienne Fitzpatrick’s nonfiction Instructions for a Flood: Reflections on Story, Geography and Connection.

In many ways, Instructions for a Flood is a quintessential Caitlin book, in the very best sense. Fitzpatrick writes from a position of humility, making room for her readers to learn and grow right along with her, but if you’re not from around here (ie, central to northern BC: which for me is “there” rather than “here,” if you see what I mean), well, she’s not making it easy for you.Let me be specific. If you’re not from her area but want to get everything you can from the experience of reading Instructions for a Flood, then you’ll just have to accept that you’ll have to learn a bit of the geography and the place’s cultures, along with all the other threads that would speak to folks already living there. The people already living there don’t need that bit, but this means they’ve automatically got deeper access to all those other threads (and I’m so envious of them!).

The book’s organized almost entirely around bodies of water, in this region that’s defined by uplifts of mountain, deep valleys between, and water almost everywhere that isn’t vertical. The sections in chapter two, for example, are entitled “Purden Lake,” “Mud River,” “Eaglet Lake,” and “Fraser River Headwaters.” Of those four, only two appear on the map that’s placed after the table of contents. To some extent, you don’t need to know the places with any precision, but on the other hand it’s helpful to know which communities are near these places. Vanderhoof isn’t Prince George isn’t Fort St. James, and there are (for example) different risks to being alone as a woman at a nearby lake.

But humility: Fitzpatrick’s a local, in that she grew up in Vanderhoof, but she’s at pains in this book to make sure her readers recognize that her subject position isn’t deeply that of an insider (“How can you not like country [music]?,” one character asks. “You’re from here” [p.52). While driving with her family to visit Ormond Lake, Fitzpatrick and her aunt share this same experience of listening to the intersecting stories of the more knowledgeable among them, which I take to be the same experience she expects her readers to have:

“We are the listeners, the messengers who bring the story back for the others, add a few lines of our own” (p.39).

The trip to Ormond Lake is a classic trip for families in the region, too, a long drive just to check out a place they haven’t seen for a while, but a place that’s not especially meaningful or scenic or momentous. At the end of the day, stories swapped and places seen, the circle just gets quietly closed: “We pile back in the new Jeep, bare branches squeak along the sides as we pass, soft spruce needles we can hardly hear” (p.40). She does remark (or more likely her mother does — without quotation marks, it can be hard to tell) that it’s “amazing what comes up when you go down some roads,” but the whole region reads like home, no matter how much or how little connection Fitzpatrick has to the specific places.

And in many cases, in spite of her family connections, Fitzpatrick has very little connection to these highly specific places. She’s a settler, period, but it’s important to note that she’s a settler who’s supporting the region’s Indigenous people and peoples by helping them represent themselves. In “Kemess Lake,” for example, one of the longest sections, she helps some Tsay Keh Dene elders hike an ancient trail that’s not far from a planned massive conveyor belt associated with an even more massive mine, so that the belt can be routed away from culturally significant sites: an ancient deadfall trap, for example, or culturally modified trees. Although politically speaking, many kinds of risks and complications are present in this sort of activity, it’s work that can allow a settler to connect with a place, and that’s just Fitzpatrick’s slowly earned experience:

“Triumph that we’ve made it [through the hike] shows in our smiles in the picture Rich takes of us, though I didn’t feel it. It sank in later, warm glow mixed in with fatigue, bruises revealing new lands traced on my body” (pp.84-85).

It’s a joy, this small volume, and though I’m writing dangerously near to Christmas, I’d love to hear that some folks bought copies of Instructions for a Flood for their friends and families, especially in the area that Adrienne Fitzpatrick documents in this book. Several years ago, I taught Fitzpatrick’s first book in an undergrad class on BC literature, The Earth Remembers Everything; the students responded really thoughtfully, even before she Skyped in for a conversation, and my sense is that this one would work even better.

Because the thing is, ancient stories of ancient floods (yes, the repetition is intentional) occur all over British Columbia. Lakes like the ones Fitzpatrick are nearly infinitely numerous in BC because of those floods, and climate change will bring with it all kinds of changes. We need these stories, and other stories, and we need to know the lakes and the land and all the people we share it with.

Books like this, genuinely, represent instructions for a flood, and a flood’s exactly what we’re going to face. It’ll be important to have gathered a sense of community around us, before much longer.

Comments