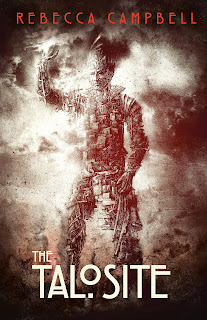

Rebecca Campbell, The Talosite

The novella, being a smaller version of the novel, always needs to take on smaller topics, narrower stories, more modest themes, because....

What trash. No, the novella gives its author the opportunity to muck about generatively, gives them more freedom to experiment and gesture and suggest, without any compulsion toward a sense of completeness. At their best, novellas are remarkable in their own right, needing to be read and experienced as a completely separate genre from the novel. (Genres are made up anyway, mostly an imposition by advertisers and PR intended to translate a breathing culture into a repeatably manufacturable commodity, but but but.)

Which brings me, of course, to Rebecca Campbell's weird, unsettling, horrible, deeply satisfying novella The Talosite.

An alternative history focused on the total war across Europe between 1914 and 1918, what in our world is known now as World War One, The Talosite follows young Anne Markham's brief career as the most brilliant of the ingenieurs, those on the British/French side charged with the mission of redesigning and reanimating corpses for military use. As the back cover has it, "They're all dead, but dead doesn't always mean what it used to."The shadow of Frankenstein looms large over the book, of course, but not in a precise way. Like Mary Shelley with her father William Godwin (her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft having died shortly after her birth), Anne Markham is raised by her father toward something like the family business. Shelley became a writer / thinker like her father, in a complicated sense; in a similarly complicated sense, Anne Markham becomes a doctor / technician / inventor.

Among other things, Anne and her father both experiment on their own bodies (Anne after her father's death) in order to develop the knowledge and skill to manufacture and enable ever more advanced ... well, beings, I guess. They're referred to by various terms in the book, including automata, but Anne's eventual term for them, once she reaches a high degree of proficiency, is Talosite. (Please enjoy the grand rabbit hole of Greek myth about the figure of Talos, who was said to have been a bronze giant made by Zeus to protect his beloved Europa, after whom the continent of Europe was named!)

Anne's largely self-appointed task is to create ever larger, ever more complicated Talosites to play different roles in the defeat of the German forces and their own automata. By the end of the novel, she's creating Talosites with multiple heads, using the body parts of numerous species as well as various metals, all knitted together with tiny stitches. The reanimation of these creatures, by both sides in the war, is controlled by various strains of lazarites: no, not the Catholic followers of St. Vincent de Paul, but mushrooms.

I've had to try NOT to include a manifesto here about the idea that basically the world's just being farmed by fungi for their own benefit, including the ecology of human death when there are this many billion people on the planet, but that's not in the book itself. I don't think Campbell's a series author, so to speak, so I don't expect more from the world of The Talosite, but it'd be fascinating. In the backstory, for example, there are stray mentions of "wild" automata, without explanation except that they seem to have been under the influence of fungal infections. The German side and the British/French side use different stains of fungi for their reanimations, too, so there's a whole universe available just in that little arena. All that's implied, even if only barely, in The Talosite, so I found it genuinely strange to be holding such a thin volume.

And yet in under 130 pages, this sweeping military epic is also a suffocatingly small story, rendered with intimate, poignant detail.

Anne, the main character, is recovering from successive smashes of trauma, the whole time that she's experimenting on her own body and on various corpses, building her Talosites while working near the unending slaughter of trenches. This includes the deaths of not just her father, but her fiancee and the infant born after her fiancee's death. We see Anne in various interior spaces, mostly, her labs and her bed, and everything's always dirty and bloody and threatened. At one point she tells one of her Talosites that she is his mother, too, so it's not a stretch to read her work with the Talosites as in one respect a working out of motherhood and parenting. (The body horror is more intense than the one resulting from my own parenting, but I kind of get it. Don't judge me.)

The secondary main character, Ned, is a soldier at the front who becomes a stretcher-bearer recovering both German automata and his own side's talosites, as well retrieving bodies for Anne's facilities. He experiences the same oppressive atmosphere that Anne does in her various interior spaces, but his time outdoors is no less oppressed: it's total war, as I say, but we get both the sweep of history and the impact on individuals.

The ending is allusive and strange and frankly I really enjoyed it. Some readers haven't, I see from reading reviews, wanting more precision, but I know what I think happens next, and I am here for it. I don't want to say more here, but maybe in the comments (there are never comments on my posts, sadly), but SO MUCH YES.

Finally, I can't recommend enough this interview between Rebecca Campbell and Ariel Marken Jack. It's deeply insightful about Campbell and her two 2022 novellas The Talosite and Arboreality, both of them putting incredible thought into the process, and there aren't even any spoilers!

Comments